The European market must, till now, have been something of a frustration for U.S. red oak suppliers. The species is America’s most prolific hardwood, so, in those terms, its most sustainable. In the U.S. itself it’s used extensively in a huge range of construction, interiors and manufacturing applications, while other markets, such as China and Japan, also can’t get enough. But in Europe red oak has lagged some way behind its ubiquitous U.S. white cousin in popularity.

The market breakthrough it’s needed, say admirers, has been a major showcase project to demonstrate its aesthetic and performance appeal. Well now it has one – and wow. They don’t come much more major or more showcase than the just opened 1.1 million ft2 European headquarters of global financial data, software and media colossus Bloomberg.

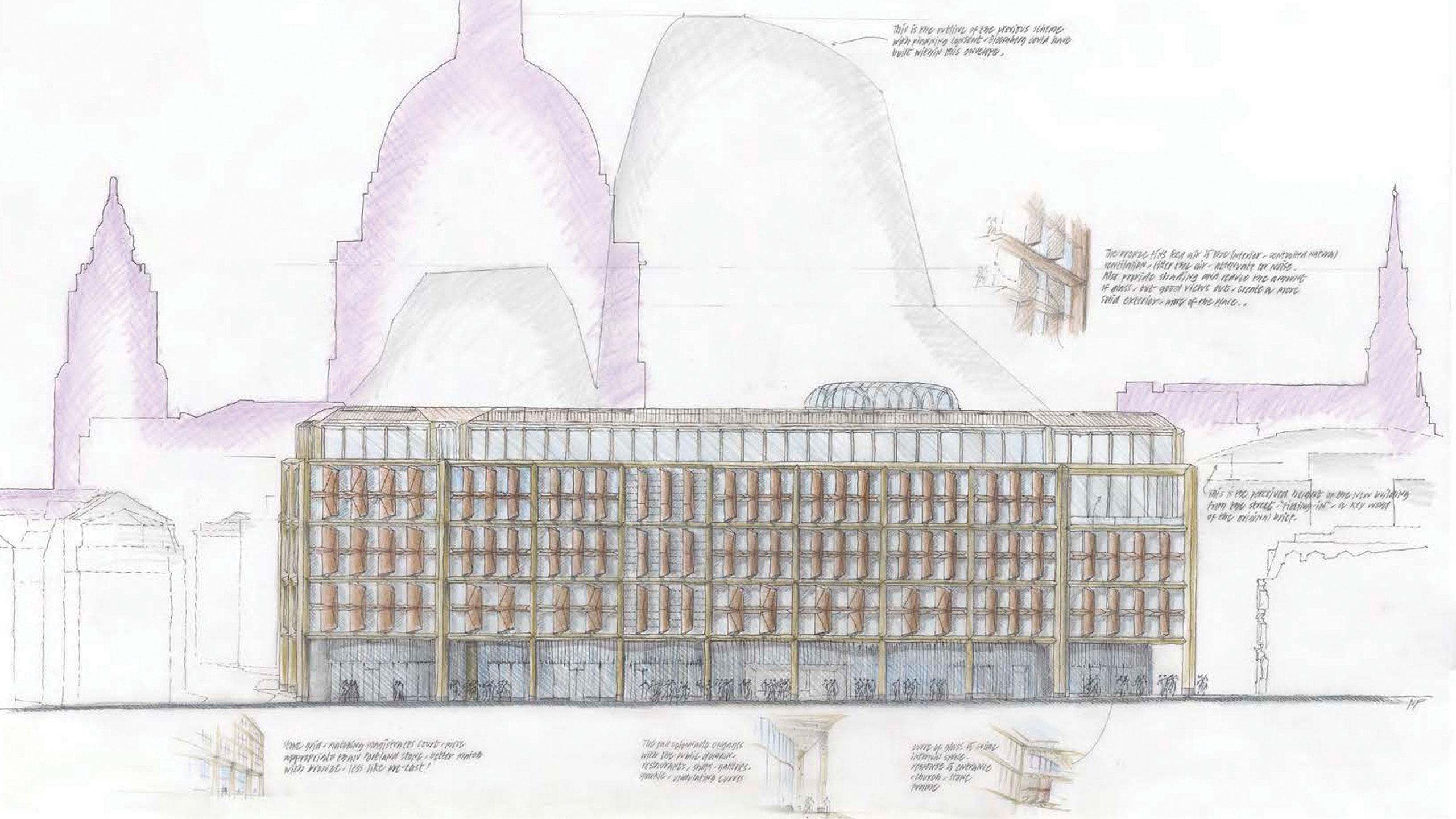

Designed by a Foster + Partners team, led by Norman Foster himself, the stunning City of London building, is already being lined up for architectural awards. It’s also scored on the environmental front, achieving a record BREEAM rating for an office development of 98.5% and being given the status of the world’s most sustainable office building.

Making the building more significant for red oak still, project architect Michael Jones said the timber is not used in any token, decorative way. It’s core to the interior aesthetics and to delivering on the designers’ wellbeing and environmental goals. It’s also used in considerable quantities – 37,160 m2 for the floor alone.

To answer the question why wood in the first place, and so much of it, Mr. Jones tracks back to initial conversations with Bloomberg CEO Michael Bloomberg.

“Previously the company has occupied existing commercial space, but establishing their European headquarters, they felt, deserved something bespoke and tailored to the way they operate,” he said. “As well as expressing this through the architecture itself and while wanting the building to be very much of its own time, they also wanted it to be very contextual and historically rooted in its place through the palette of materials. Hence the extensive use of bronze and Derbyshire stone – 9,000 tonnes of it – but equally timber, all of which you see quite typically around London. The task was to take these materials and use them in a fresh, innovative way.”

Sustainability also led Foster to timber.

“By this we mean not only that timber is renewable, energy efficient, carbon rich and all those other good things, but that it helps achieve sustainability in the broadest sense,” said Jones. “The sustainability of a building is also about the well-being of people – and people feel better in a place featuring natural materials.”

While some discount red oak because of its pinkish hue it was this, combined with its technical properties, that actually helped decide its choice for Bloomberg and Foster. “We wanted a species with warmth that would mellow and mature with age,” said Mr. Jones.

Architects and client did consider other species, but cherry was discounted due to its tendency, in certain circumstances, towards significantly darkening on exposure to light. It was also felt the white oaks of Europe and the USA would produce a finish that was too light in colour, with a more ‘yellowy hue’. The fact that the U.S. produces red oak in such volumes also played in its favour.

“Although there were still times I was nervous about whether we’d get the amount we needed in the time allowed, and with the homogeneity of grain and colour required,” said Mr. Jones. “We were asking an awful lot of the U.S. timber industry, but they rose to the occasion.”

The significance of red oak to the interior aesthetic is obvious from the moment you enter the lobby. In fact it helps make the building’s dramatic opening statement. Called the Vortex, this dramatic swirling space features 1,858 m2 of red oak cladding on its intersecting arching walls.

“The Vortex is a literal and metaphorical modern twist on the timber-lined entrance hall you find in so many classical English buildings, particularly in London,” said Mr. Jones.

This application is also one example in the building, as he describes it, where innovation has overcome the potential challenges of using wood.

“Having this much vertical cladding risked reverberation, so the timber was micro-perforated by laser. This makes it absorbent of sound, while the aesthetic is unaffected as the holes are so small. You can’t see them until you’re about 20mm from the surface,” he said.

Red oak also features prominently in the multi-purpose room, a flexible space for meetings and presentations adjacent to the building’s auditorium. Here it is used in the form of glulam, a total of 1350 m3, comprising the ‘fin walls’ which define the space.

The daring decision also to use timber for the flooring came out of a New York meeting between Michael Bloomberg and Mr. Jones and posed perhaps the biggest technical test.

“We were talking about possible flooring types and he just asked, why can’t we use wood?” said the latter. “The key reasons you don’t often see it in offices is footfall noise – and there is capacity for just shy of 7,000 people in the Bloomberg building – and the need to access the services beneath. We wanted the aesthetic of a seamless, monolithic surface, but using conventional tongue and groove boards would cause huge problems getting to all the communication cabling and other systems.”

Once more innovation overcame technical and functional hurdles. Teaming up with contractor and building systems and materials provider Kingspan, Bloomberg devised a solution where individual boards could be lifted and refitted at will.

“Each board has a magnetic strip running its length, which sticks it to the metal access floor below,” said Jones. “So you can sucker one up, lever up the surrounding boards then just drop them back into place.” This approach also means zero creaking, while the sound of footsteps is deadened by an additional acoustic layer between board and access floor. It’s also straightforward to replace any areas that suffer damage.

So convinced were Kingspan by the flooring solution, they’ve now brought it to market, and it’s already been used in a number of other projects.

Using red oak in these various applications was also a logistical exercise. Over and above sourcing it – and it all had to be FSC verified sustainable or equivalent – and shipping it over the Atlantic, the Vortex paneling was laser perforated in Switzerland, the multi-purpose room glulam walls made in Germany and the flooring machined in Italy.

The timber will need maintaining, but this should be minimal thanks to the combination of oil finish on the floor, lacquer on paneling and the material’s inherent natural durability. And if added testimony to the latter were needed, it is also housed in the new building. It’s constructed on the site of the Roman temple of Mithras and fresh remains, including structural timber elements, were uncovered during foundation excavations. Among other discoveries were 400 timber writing tablets and some of these and other artefacts are now on public display in what Bloomberg describes as a ‘free new cultural destination’, the London Mithraeum, deep in their building’s basement.

As to whether the project will inspire Foster to use red oak again, Mr. Jones’ response is why not? “We used to be best known for our use of steel and glass, but the commercial market is changing and we’re using more timber generally,” he said. “Businesses now want their buildings to have a different sense of personality and be more responsive to people who work in them. Timber is rather successful in delivering both these things. People warm to it and it makes them feel better about their environment. And, while each building is the result of conversation between client and architect, for sure we may use more red oak. Bloomberg loves the result it’s delivered and so do we.”

Architect: Foster + Partners

Wood species: American red oak

Photographer: Nigel Young, Foster + Partners, James Newton, Aaron Hargreaves

AWARDS:

Winner of the RIBA Stirling Prize 2018

Winner of the Structural Timber Awards project of the year 2018